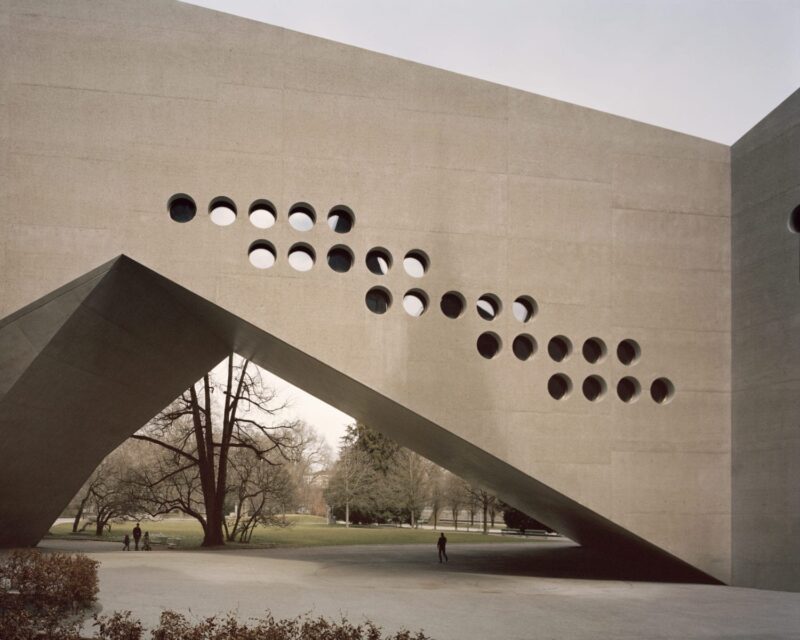

Barkow Leibinger利用兩極對立之間的張力,在美學和功能上創造了非凡的建築。他們的設計喚起了古典現代主義的靈感,同時直麵未來。

Drawing on the tension between polar opposites, Barkow Leibinger creates extraordinary architecture, both aesthetically and functionally. Their designs evoke classical modernism while gazing squarely into the future.

在一排排時髦的漂亮自行車之間,矗立著一座巨大的鐵結構建築。再往上走幾步,在夾層的模型製作車間裏,機器還在運轉,機器嗡嗡作響,捆紮、折疊、成型直接鄰接在包圍數字銑床的玻璃盒上,裏麵裝著數字銑床、激光切割機等神秘的高科技工具。

Nestled between a handsome collection of hipster bicycles stands a colossal iron structure.A few steps up, in the model building shop on the mezzanine floor, the operation is still up and running—machines hum along, bundling, folding, and forming directly adjacent to a glass box encasing a digital milling machine, laser cutters, and other mysterious high-tech tools.

采訪檔案 |Barkow Leibinger 德國柏林 | 建築師

在樓上明亮通風的閣樓裏,一群人坐在電腦前。在Jac Jacobsen設計的經典挪威Luxo燈具的照射下,整個房間沉浸在一片靜謐之中。正是在這裏,Barkow Leibinger開辟了創造他們作品的空間。

A scattering of people are seated at computers in the bright airy lofts above. A concentrated silence permeates the rooms, bathed in light cast by the classic Norwegian Luxo lamps designed by Jac Jacobsen. It is here that Barkow Leibinger have opened a space in which to create their work.

“我們的工作流程是做事和思考的辯證法。”Frank Barkow解釋道,“來來回回,你可以將這個過程智能化,當然這個概念很重要,但從本質上講,它是關於材料的。它是關於嚐試新舊工具以及表單本身。這個概念隨項目而來,但最終都回歸到設計中。”這種持續不斷的辯證法,其根源在於該公司創始人之間的頑皮對立的力量,他們之間的差異大得不能再大了。比如來自蒙大拿腹地的Frank Barkow,他是一位“磚匠”,也是一位有著一千個想法的修補匠,在活躍的對話中,他的手指會飛到桌子上方,就好像在尋找鋼琴鍵、蠟筆或錘子。還有Regine Leibinger,她是一位商業大亨的女兒和一位藝術品交易商孫女,接受過古典教育,在這一過程中學會了斯瓦比亞式的經商技巧。

“Our work flow is a dialectic of doing and thinking. A constant back and forth,” explains Frank Barkow. “You can intellectualize the process, of course the concept is important, but at its core, it’s about the material. It’s about experimenting with old and new tools and with the form itself. The concept comes with the project, but it all comes back around to the design.” This ongoing dialectic has its origins in the playfully opposing forces of of the company’s founders, who couldn’t be more different. There’s Frank Barkow from deep Montana, a “Bricoleur” and tinkerer with a thousand and one ideas, whose fingers fly over the table top during animated conversation, as if in search of piano keys, a crayon or a hammer. And then there’s Regine Leibinger, the bubbly business magnate’s daughter and granddaughter of an art dealer, who was given a classical education and acquired a Swabian knack for business along the way.

B-L Schaufenster是Barkow Leibinger的畫廊空間。

B-L Schaufenster是Barkow Leibinger的畫廊空間。

不太可能的一對。然而,當這兩個人在90年代早期第一次在哈佛大學見到時,就一見鍾情了。“這真的很有趣,”Barkow回憶道,“Regine非常理性,非常歐洲化——非常老練。我更有實驗精神和表現力。但我們對空間和材料都很敏感。”“是的,”Leibinger附和道,“我們都是從空間布局的角度來考慮的。建築立麵,天花板,屋頂,第五立麵。我們對材料有著同樣瘋狂的興趣。我的總是具體的,對弗蘭克來說,基本上什麼都是。但是我們當時的觀點完全不同。”

An unlikely pair. And yet, it was love at first sight when the two first met at Harvard University in the early ’90s. “It was really funny,” recalls Barkow. “Regine was very rational, very European—so sophisticated. I was more experimental and expressive. But we shared a sensitivity to space and materials,” he adds. “True,” Leibinger chimes in. “We both always thought in terms of spatial layouts. And about building facades, ceilings, roofs, the fifth facade. And we shared this insane interest in materials. Mine was always concrete and for Frank, oh, basically everything. But our perspectives at that time were totally different from one another.”

這也就不足為奇了。畢竟,Berlin剛剛走出柏林,後現代主義在80年代早期風靡一時。學生們都在學習密斯·凡德羅(Mies van der Rohe)和布魯諾·陶特(Bruno Taut)等人的住宅建築。當時的國際建築展覽涉及“批判性重建”和約瑟夫·保羅·克萊休斯(Josef Paul Kleihues),這讓Berlin重新認識了彼得·艾森曼(Peter Eisenman)和路易·卡恩(Louis Kahn)等美國建築師。

And it’s no wonder. After all, Leibinger was fresh out of Berlin, where postmodernism was all the rage in the early ’80s. Students were learning about residential architecture from the likes of Mies van der Rohe and Bruno Taut. The International Architecture exhibition at that time dealt with “critical reconstruction” and Josef Paul Kleihues, which opened Leibinger’s eyes to American architects like Peter Eisenman and Louis Kahn.

這些是Frank Barkow在入讀哈佛大學之前沒有聽到過的名字。“我從不知名的地方來到這裏。蒙大拿州與建築語言相去甚遠,所以我認識的第一批建築師是巴克明斯特·富勒(Buckminster Fuller)和安特農場(AntFarm)。或者布魯斯·戈夫(Bruce Goff)和他的偶像弗蘭克·勞埃德·賴特。”在蒙大拿州廣袤的土地上,巴克成長於以農業和重工業為特征的建築之中——鐵路、水壩、采礦和木材。“基礎設施不僅僅是建築,真的。到目前為止,景觀和建築之間的這種聯係對我來說仍然非常重要,”Barkow說,“蒙大拿州的這些小山城擁有19世紀淘金熱時期建造的美麗建築典範。這也是為什麼我愛上了藝術家唐納德·賈德(Donald Judd),他說,美國最美的東西都是由工業塑造的。”

These were names which Frank Barkow hadn’t heard much about before enrolling at Harvard. “I came literally from the middle of nowhere. Montana was pretty far removed from architectural discourse, so the first architects I knew were Buckminster Fuller and AntFarm. Or Bruce Goff and his idol Frank Lloyd Wright.” In the vast lands of Montana, Barkow grew up with architecture that was marked by agriculture and heavy industry—railroads, dam buildings, mining, timber. Infrastructure more than architecture, really. “This connection between landscape and building is still very important to me to this day,” says Barkow. “These small mountain towns in Montana have beautiful examples of architecture that were created during the gold rush of the 19th century. That’s also why I came to love the artist Donald Judd, who said, the most beautiful things in the USA were shaped by industry.”

高中畢業後,這位十七歲的孩子開始用簡單的工具建造木屋。 正如他的妻子Regine所說,他對建築有了直觀的“本土理解”。但最終是美國人的自我決定,一種為自己思考和做事的態度,促使他學習建築。“從一開始,我就很得心應手,我有自己動手蓋房子的技能。但是Regine所用的所有知識和參考資料都很有趣,我必須一步一步地慢慢地學習。”

After finishing high school, the seventeen-year-old started building wooden houses with simple tools. He developed an intuitive “native understanding” of architecture, as his wife Regine puts it. But ultimately it was American self-determination, the attitude of thinking and doing for yourself, which led him to study architecture. “From early on I was pretty handy, and I had the manual skills to build houses on my own. But all the knowledge and references that Regine used so playfully, I had to learn the hard way, slowly, step by step.”

模型製作車間是Barkow Leibinger的設計師動手的地方。他們利用激光切割機和3d打印機等新興技術,將新的建築理念打造成定製的微縮模型,讓每個人都能觸摸到。

模型製作車間是Barkow Leibinger的設計師動手的地方。他們利用激光切割機和3d打印機等新興技術,將新的建築理念打造成定製的微縮模型,讓每個人都能觸摸到。

然而,正是由於他們截然不同的方法,Barkow Leibinger的作品才如此特別。在比賽取得初步成功之後,美國的經濟衰退以及斯圖加特的狹隘思想將他們引向了後柏林牆時代的柏林,當時的柏林正隨著社會變革、藝術、音樂和攝影而飛速發展。他們的第一間辦公室位於Regine在Schöneberg的舊工作室公寓內。1998年,他們在斯圖加特附近的迪津根建造了屢獲殊榮的Trumpf工廠,從而取得了突破性進展。

And yet it is due to their disparate approaches that the work of Barkow Leibinger is so special. After some initial success at competitions, the recession in the US and and the narrow mindedness of Stuttgart pointed them in the direction of newly post-wall Berlin, which was pulsating with social change, art, music, and photography. Their first office was situated in Regine’s old studio apartment in Schöneberg. Their breakthrough followed soon after in 1998 with the award-winning Trumpf laser factory in Ditzingen, close to Stuttgart.

當Frank Barkow與Regine的父親Berthold坐在一張桌子旁時,兩人之間不可否認地擦出了火花。Berthold是一位真正的修補匠和藝術愛好者。“Berthold是一位德國天才,”Barkow盛讚道,“他像工程師和詩人一樣思考。他給了我們自由,但也給了我們適當的反擊,隻有通過Trumpf,我們才找到了通往金屬的道路。”

When Frank Barkow sat down at a table with Regine’s father Berthold, a true tinkerer and art lover, there were undeniable sparks between the two. “Berthold is a German genius,” Barkow raves. “He thinks like an engineer and a poet at the same time. He gave us freedom but also the right amount of push back, and it was only through Trumpf that we found our way to metal.”

這個故事多少讓人想起沃爾特•格羅皮烏斯(Walter Gropius),他為卡爾•本謝德(Carl Benscheidt)在阿爾菲爾德建造了如今著名的法格斯工廠。它是所謂的Fagus-knot,兩個交叉的橫梁,允許Gropius使用鋼框建造落地窗,而不使用可見的結構支撐,從而產生開放感。Barkow Leibinger在很大程度上要歸功於他們與著名工程師Werner Sobek的合作,如果沒有他,他們就不會創造出Trumpf食堂巨大的屋頂結構,食堂坐落在幾根細絲鋼柱上。屋頂上的多邊形、部分上了釉的木質蜂巢不僅是家居裝飾,它們還能吸收食堂裏一些噪音很大的哢嗒聲和喋喋不休的聲音。下麵的空間可以很容易地變成畫廊、禮堂或聖誕派對的場地。“但是,當然,你也可以在那裏吃Maultaschen,這是非常重要的。”Barkow補充說。

This story is somewhat reminiscent of Walter Gropius, who built the now famous Fagus Factory in Alfeld for Carl Benscheidt. It was the so-called Fagus-knot, two crossed beams, which allowed Gropius to construct floor to ceiling windows using steel frames without the use of visible structural support, resulting in a sense of openness. Barkow Leibinger owe a great deal to their collaboration with the renowned engineer Werner Sobek, without whom they wouldn’t have created the massive roof construction of the Trumpf Canteen, which rests on a few filigree steel columns. The polygonal, partially glazed wooden honeycombs that populate the roof are not just homely ornaments, they also absorb some of the the noisey clatter and chatter of the canteen. The space below can easily transform into a gallery, an auditorium or a venue for a Christmas party. “But, of course, you can also eat Maultaschen there, which is very important,” adds Barkow.

在技術和材料以及生產方法上的創新,似乎豐富了Barkow Leibinger的藝術創造力。Albert Kahn在底特律的福特工廠標誌著“福特主義”的開始,這不僅改變了工業生產,也改變了整個社會。Regine Leibinger解釋說:“這是我們第一個使用工業4.0原理建造的建築。”的確,俯瞰控製室中的巨型顯示器機房,配有彎板機和激光切割台,這些讓人想起史蒂文•斯皮爾伯格(Steven Spielberg)《少數派報告》(Minority Report)中的科幻幻想。

Innovations in technology and materials as well as production methods seem to fertilize the artistic creativity of Barkow Leibinger’s designs. Albert Kahn’s Ford factory in Detroit marked the beginning of “Fordism”, which not only changed industrial production, but also society as a whole. In the not-so-distant future, one might look back and see Barkow Leibinger’s Smart Factory for Trumpf in Chicago as a pioneering piece of industrial construction. “It’s our first building created using the principles of Industry 4.0—the digitized, globally linked production network utilizing artificial intelligence,” explains Regine Leibinger. Indeed, the giant displays in the control rooms overlooking the machine rooms with the plate bending machines and the laser cutting stations are reminiscent of the science fiction visions in Steven Spielberg’s Minority Report.

步入式檔案館,獲獎設計的微縮模型放在與學生一起完成的投機性研究模型旁邊。

步入式檔案館,獲獎設計的微縮模型放在與學生一起完成的投機性研究模型旁邊。

為了抵消高科技設備的豐富,通風的門廳覆蓋著溫暖的鬆木,立麵小心翼翼地生鏽。畢竟,芝加哥位於美國“鐵鏽地帶”的邊緣,而“鐵鏽地帶”是美國汽車工業的心髒地帶,如今已不複存在。Barkow解釋說:“在某種程度上,這個建築已經過時了,但是仍然在不斷進步。”“我們結合了美國工業曆史的材料和美學——鋼鐵、密斯·凡德羅(Mies van der Rohe),以及美國高速公路的建設——唐納德·賈德(Donald Judd)認為,高速公路上的橋梁和標誌對美國文化產生了重大影響——並將它們與工業4.0的高科技新工藝相結合。”這就是我對它如此感興趣的原因。”

To counteract the abundance of high-tech gear, the airy entrance hall is covered with warm pine wood and the facade is left discreetly rusted. Chicago is, after all, at the edge of the American rust belt, the now defunct heart of the old American automobile industry. “The architecture is archaic on some level while still managing to be progressive,” explains Barkow. “We tie in the materials and the aesthetic of American industrial history—steel, Mies van der Rohe, and the construction of the American freeway, whose bridges and signs, according to Donald Judd, are a major influence on American culture—and combine them with the new high-tech processes of industry 4.0. That’s what makes it so interesting for me.”

Barkow Leibinger將傳統、工藝、數字化和審美精準結合在一起,形成了具有清晰功能的空間設計藝術概念,這種獨特的方式可以在他們位於柏林的美國學院展館中看到。玻璃屋為學院的學者們提供了令人愉快的簡單工作空間,可以俯瞰位於德國首都西南方向的大旺西湖。它讓人想起密斯·凡德羅的範斯沃斯住宅的當代變體,但屋頂結構複雜,采用了鋼結構。這個想法源自一位摩洛哥織布工,他向Barkow Leibinger展示了自己有數百年曆史的手藝,然後把它帶到柏林,在那裏,研究小組對地毯進行了數字化、縮放,並把地毯的質地變成了一個巨大的裝置,由1001根鬆木懸掛的棉線組成,用於馬拉喀什雙年展(Marrakech Biennale)。這個雙曲線結構的元素現在高聳於 Greater Wannsee頂上。

The particular way in which Barkow Leibinger weaves together tradition, craftsmanship, digitization and aesthetic precision into an artistic concept of spatial design with clear functionality can be seen in their pavilion for the American Academy in Berlin. The glass bungalow offers the scholars of the academy delightfully simple workspaces overlooking Greater Wannsee, a lake located in the south west of the German capital. It evokes a contemporary variation of Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House, but with a complicated, offset roof structure made of steel. The idea for this was born from a Moroccan weaver, who showed Barkow Leibinger his centuries-old craft, which was then taken to Berlin where the team digitized, scaled, and transformed the texture of the carpets into a gigantic installation made of 1,001 pine-suspended cotton threads for the Marrakech Biennale. Elements of this hyperbolic structure are now towering over the heads of the fellows at Greater Wannsee.

Frank Barkow說:“我們也將我們的辦公室視為一個研究平台。”“當我們看到一個問題的潛力時,我們會把它帶給哈佛和普林斯頓的學生,在那裏我們可以以極高的水平來解決它。“這正是Chris Bangle為寶馬公司設計的一款烏托邦式的汽車如何轉變為靈活、可持續的經濟適用房結構。就像在他自己的辦公室裏一樣,正是這種動態的緊張關係,一種以眼睛的高度看待事物的方式,對最佳解決方案的懷疑和掙紮,讓Barkow對哈佛“艱苦的教育”心存感激:“我需要這種抵抗,”他堅持說。“這些年輕的、充滿幹勁的學生向我挑戰,”Leibinger證實道。“當涉及到新技術、新材料和新視角時,他們也讓我跟上時代。”

“We also see our office as a research platform”, says Frank Barkow. “When we see potential in a problem, we take it to our students at Harvard and Princeton where we can work on it on at an extremely high level.” This is exactly how a utopian car design that Chris Bangle made for BMW turned into flexible, sustainable structures for affordable housing. Like in his own office, it is this dynamic tension, a way of approaching things at eye level, the doubts and the struggle for the best solution, that Barkow appreciates about the “tough schooling” of Harvard: “I need this resistance,” he insists. “These young, very motivated students challenge me,” confirms Leibinger. “They also keep me up to date when it comes to new technologies, materials, and perspectives.” The best ones tend to join their office in Berlin, a city whose creative energy the two swear is second to none.

在從他們選擇的城市中汲取無限靈感的同時,Barkow Leibinger用他們自己的建築慢慢塑造柏林的城市景觀。像是2012年中央火車站(火車總站)總體規劃項目的旅遊總部大樓,或Neukölln的Estrel塔,它將成為該市最高的建築。建築師們甚至在推動傳統的保守開發商,比如柏林的一家房屋建築公司,將創新方法融入到他們的建築實驗中。“這種由柏林理工大學土木工程師Mike Schlaich開發的新型建築材料令人驚歎:它不僅支持和保護材料免受磨損,而且還提供絕緣材料,並且完全可回收利用。我們是第一次用這種材料建造高層建築。” Leibinger解釋道。

While drawing infinite inspiration from the city of their choice, Barkow Leibinger slowly shape Berlin’s urban landscape with their own buildings. Just take a look at the elegantly twisted Total skyscraper at the main train station from 2012, or the Estrel Tower in Neukölln, which is slated to be the tallest building in the city. The architects are even moving traditional conservative developers like a Berlin housing construction company to integrate innovative methods into their building experiments. “This new building material developed by civil engineer Mike Schlaich at the TU Berlin is amazing: it not only supports and protects the material from wear and tear, it also provides insulation and is fully recyclable. We are making a highrise out of the material for the first time,” explains Leibinger.

幾年前,Barkow Leibinger實現了他們在紐約擁有一間辦公室的老夢想。“我對美國建築非常不滿,”Barkow說。“我認為我對建築的歐洲化理解可以幫助它變得更好。”按照勒柯布西耶(Le Corbusier)、埃裏希門德爾鬆(Erich Mendelsohn)和其他流亡建築師的傳統,他們在20世紀二三十年代幫助塑造了美國的建築文化,來自蒙大拿州深處的美國建築師弗蘭克·巴科(Frank Barkow)回到祖父的土地上,將教育,藝術感和建築文化帶回美國。即使紐約辦公室還處於起步階段,Barkow也喜歡這種說法。 這是理論上不太可能但實際上卓有成效的組合之間的又一個橋梁:Barkow和Leibinger。

A couple of years ago, Barkow Leibinger made their old dream of having an office in New York come true. “I’m pretty critical of American architecture,” says Barkow. “And I think my Europeanized understanding of architecture can help to make it better.” In the tradition of Le Corbusier, Erich Mendelsohn and other exiled architects who helped to shape American building culture in the 1920s and ’30s, Frank Barkow, an American architect from the depths of Montana, returns to the land of his grandfathers to import education, a sense of art and architectural culture back into the USA. Even if the New York office is still in its infancy, Barkow enjoys this narrative. It is yet another bridge between this theoretically unlikely but practically fruitful combination: Barkow and Leibinger.

本文是《建築師對話》係列的一部分,由Freunde von Freunden和西門子家用電器公司共同製作,他們采訪了四位獲獎建築師和室內設計師來探討當代設計理念、城市生活趨勢和全球挑戰。

This story is part of Architect Dialogues, an interview series by Freunde von Freunden and Siemens Home Appliances that explores current design philosophies, urban living trends, and global challenges with four award-winning architects and interior designers.

版權歸屬

Text © Sarah Elsing for FvF Productions

Photos © Daniel Gebhart de Koekkoek for FvF Productions